Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction

Every day, we engage with a complex web of societal systems, often unaware of how deeply these structures shape our lives. From the careers we pursue and the products we buy to the beliefs we adopt, these systems influence our choices and, in many ways, define our place in the world. But a critical question emerges: Are we merely inputs in a larger system, contributing to a machine built to benefit a select few?

This question isn’t intended to provoke fear or suspicion but to encourage reflection. Understanding our roles within these structures can empower us to make conscious choices, influence outcomes, and advocate for a fairer system. History reveals how, in many cases, societal systems concentrate power and resources within a privileged few, while the majority serve as the “input” — providing labor, data, or compliance that keeps the system running. Today, the dynamics of these systems are visible across many sectors, from the global economy and education to healthcare and technology.

This blog will explore these dynamics and, through framework thinking, introduce tools that can help us better understand our position within these systems. The goal? To move from passive participation to active engagement, transforming how we interact with — and influence — the systems around us.

Real-World Systems and the Input Dynamics

The concept of people as inputs to a system controlled by a select few is far from abstract. Many of our everyday experiences — our work, education, healthcare, and even our online presence — reveal a recurring dynamic: systems often designed to concentrate value at the top, while relying on the contributions of those below. Let’s examine a few real-world examples of this “input-output” model and see how it plays out in various sectors.

The Global Capitalist Economy

The capitalist economic system operates through a structure where capital owners and stakeholders — often a minority — amass the wealth generated by the work of countless employees. Workers, the primary input to this system, contribute their time, energy, and skills in exchange for wages. Yet, despite their crucial role in creating value, they rarely receive a proportionate share of the profits. Instead, most of the financial rewards flow to the top, creating wealth disparities and perpetuating inequality.

- Example: Multinational corporations with shareholder structures often see profits distributed primarily to executives and shareholders, while the average worker may experience stagnant wages and limited upward mobility.

- Implication: This economic setup, though efficient in generating wealth, poses ethical questions about fairness and the concentration of resources. Workers’ roles as inputs in this system contribute to an economy that prioritizes profit over equity.

The Education System

Education, particularly in under-resourced communities, can resemble a production line, where students progress through a standardized system with little regard for individual interests or talents. This “factory model” of education often prioritizes uniformity — a one-size-fits-all approach — over creativity and personalized learning.

- Example: Schools may focus heavily on standardized testing to measure student success, overlooking the individual strengths and potential of each student.

- Implication: In this system, students function as inputs, shaped and processed to meet standardized benchmarks rather than encouraged to explore and realize their unique potential.

Healthcare as a System of Inputs and Outputs

In many healthcare systems, particularly those driven by profit, patients become inputs whose needs fuel an industry of treatments, diagnostics, and pharmaceutical sales. The structure of healthcare in these cases tends to prioritize profitable treatments over preventive care, emphasizing short-term solutions rather than long-term wellness.

- Example: Insurance-driven healthcare systems often emphasize costly treatments over preventive measures, focusing on revenue from procedures rather than holistic health.

- Implication: Patients, as inputs, are treated more as cases to be managed rather than individuals with complex, multifaceted health needs.

Awakening to System Awareness – Framework Thinking

Recognizing the dynamics within societal systems doesn’t mean rejecting or rebelling against them outright. Rather, it’s about understanding their structures, acknowledging our roles, and exploring ways to reshape these systems to be more equitable. Framework thinking offers tools to achieve this understanding, providing structured approaches to analyze and engage with complex systems.

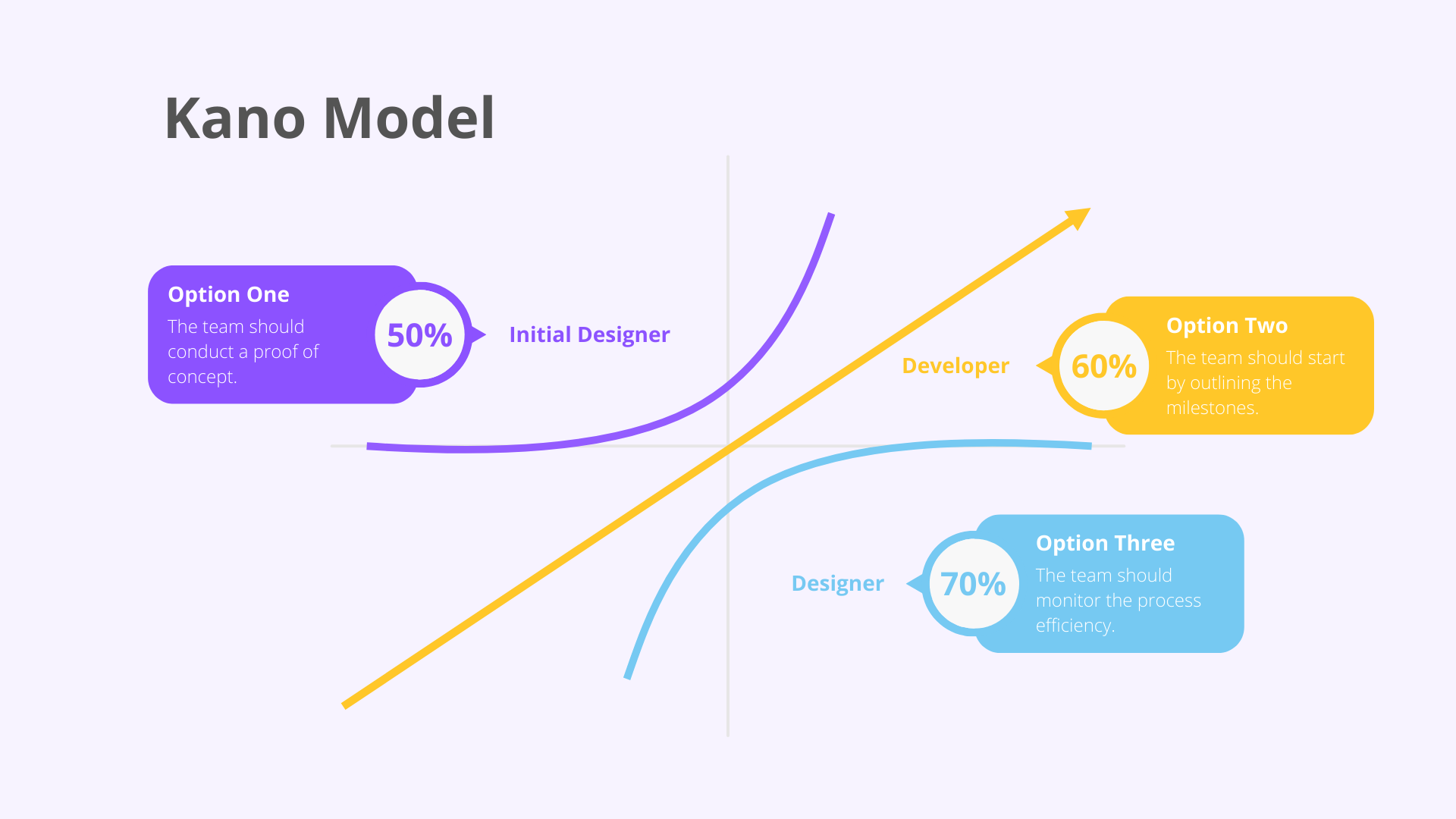

Framework thinking allows us to break down intricate systems into manageable components, making it easier to analyze power structures, identify leverage points, and develop strategies for positive influence. Let’s look at two practical frameworks — SWOT Analysis and Porter’s Five Forces — to see how they can help us understand and navigate the systems we interact with.

Applying SWOT Analysis to Your Role in a System

SWOT Analysis — which stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats — is a strategic tool used to assess a situation or entity from multiple angles. Applying SWOT to our roles in various systems can help us understand how we contribute to these systems, what challenges we face, and where opportunities for influence lie.

-

Strengths: Identify the unique skills, resources, or positions you bring to the system. For instance, as an employee, your skills and experience may be valuable assets, while as a student, your perspective and curiosity are strengths that bring fresh insights.

-

Weaknesses: Recognize any constraints or limitations imposed by the system. These might include limited decision-making power in a company or restricted educational resources in a standardized school system.

-

Opportunities: Look for ways to leverage your strengths to create a positive impact or advance within the system. In a workplace, opportunities may include skill development, networking, or advocating for inclusive policies. In education, this could mean seeking extracurricular opportunities or alternative learning resources.

-

Threats: Acknowledge the obstacles that could hinder progress or lead to adverse outcomes. These might include economic instability in an employment system, competitive pressures, or systemic inequalities that make advancement difficult.

Example: Let’s say you’re working in a corporate environment that prioritizes profits over employee well-being. A personal SWOT analysis might reveal:

- Strengths: Your expertise and experience, which contribute to the company’s success.

- Weaknesses: Limited influence over corporate policy.

- Opportunities: Chances to advocate for change by participating in workplace committees or suggesting wellness initiatives.

- Threats: Corporate policies or leadership that may resist change, favoring profits over employee health.

Using SWOT, you can identify ways to utilize your position within the system to influence positive change, shifting from a passive input to an active participant.

Using Porter’s Five Forces to Understand Power Dynamics

Porter’s Five Forces is a framework developed by economist Michael Porter to analyze competitive forces within a market. Although traditionally applied to business, it’s also useful for understanding the power dynamics in societal systems and how these dynamics influence our roles.

-

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Who controls the resources? In a workplace, this could refer to the employers or managers who control wages, benefits, and advancement opportunities.

-

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Who has control over the outputs? In education, students are often viewed as the “customers,” but in practice, the educational institutions may hold more power over the learning process.

-

Threat of New Entrants: How easy is it to change or innovate within the system? For example, disrupting traditional educational systems can be challenging due to regulation and long-standing norms.

-

Threat of Substitutes: Are there alternatives that could fulfill the same purpose? In healthcare, for instance, holistic or alternative practices may serve as substitutes for conventional treatments, impacting the system dynamics.

-

Competitive Rivalry: What competitive forces exist within the system? In employment, this could mean competition among employees for promotions, impacting collaboration and work culture.

Example: Analyzing the healthcare system through Porter’s Five Forces could reveal:

- Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Pharmaceutical companies and healthcare providers have significant influence over treatment options and pricing.

- Bargaining Power of Buyers: Patients have limited choice in healthcare providers, often dictated by insurance or availability.

- Threat of New Entrants: Stringent regulations make it difficult for new healthcare providers to enter the market.

- Threat of Substitutes: Alternative and holistic health options present a growing substitute to traditional healthcare.

- Competitive Rivalry: Hospital systems may compete for patients based on reputation, resources, or specialties.

By using Porter’s Five Forces, you gain insight into where power is concentrated within a system, helping identify which aspects are open to influence and where you might direct efforts for change.

Moving from Passive Input to Active Influence

Understanding the systems we navigate through the lens of framework thinking is a crucial first step. But awareness alone doesn’t create change. To reshape the systems that influence our lives, we must move from passive input — merely participating in the system — to active influence, where we intentionally engage and effect change within the structure.

This shift involves leveraging the insights gained from tools like SWOT analysis and Porter’s Five Forces and using them to take strategic action. Here’s a guide to applying framework insights to transform your role from a passive participant to an active influencer within societal systems.

1. Identify Leverage Points for Change

In systems thinking, leverage points are areas where small shifts can produce significant changes. By identifying and focusing on these points, you can maximize your impact within the system without expending excessive resources. Leverage points often include decision-making processes, influential individuals, or under-utilized resources within a system.

- Example: In a workplace setting, leverage points might include participating in a committee that influences policies, building alliances with like-minded colleagues, or engaging with mentors who hold decision-making power.

- Action: Use insights from your SWOT analysis to identify where you have influence and where small actions might yield meaningful results. For instance, if your strength is communication, consider advocating for changes at meetings or through written proposals.

2. Develop a Strategic Plan Using Framework Thinking

Armed with a better understanding of the system, you can build a strategic plan to implement change. Start by defining clear goals and breaking them down into achievable steps, using frameworks to guide your approach.

- SWOT and Goal Setting: Set personal or group objectives based on identified strengths and opportunities. For example, if you’ve identified a weakness in workplace policy but see an opportunity for improvement, create a proposal that emphasizes how the change aligns with both organizational goals and employee well-being.

- Porter’s Five Forces and Advocacy: Use your understanding of power dynamics to inform your advocacy efforts. If you know who holds influence within the system, tailor your message to resonate with these key players.

Example: Suppose you’re seeking changes in a healthcare setting that prioritizes costly treatments over preventive care. A strategic plan might involve:

- Setting clear goals: Reducing barriers to preventive care through policy change or patient education initiatives.

- Mapping out steps: Building support by sharing research, consulting with patient advocates, and proposing pilot programs.

3. Cultivate Relationships and Build Alliances

Systems are built and maintained by people, and creating change often requires collaboration. By building relationships and alliances with others who share your goals or values, you increase your influence within the system. Whether it’s forming partnerships with colleagues, participating in advocacy groups, or building community connections, alliances amplify your voice and create momentum for change.

- Example: In education, if you’re a teacher seeking more flexibility in curriculum choices, consider forming a coalition with other educators to advocate for a curriculum review or joining committees that make curriculum decisions.

- Action: Identify potential allies within the system and start with open dialogues. Share your vision for change and listen to their perspectives to find common ground. Working together, you can create a collective voice that’s more likely to be heard.

4. Adopt a Continuous Improvement Mindset

One of the core principles of Lean and framework thinking is continuous improvement — the idea that small, consistent changes can lead to substantial progress over time. Adopting this mindset means being open to incremental changes rather than expecting immediate, sweeping reforms. By making small adjustments, tracking outcomes, and iterating, you contribute to long-term improvement within the system.

- Example: If you work in a corporate environment that prioritizes profit over employee well-being, initiate small wellness initiatives, such as organizing short wellness sessions, creating a suggestion box for workplace improvements, or offering feedback channels. Over time, these smaller efforts can build a case for larger initiatives.

- Action: Document each small win and use it as evidence to advocate for further change. By showing how each step contributes to broader goals, you can maintain momentum and demonstrate the benefits of incremental improvements.

5. Educate and Empower Others

Systemic change is more sustainable when it’s collective. Educate others about the systems they’re part of and the tools they can use to influence change. Sharing knowledge about frameworks like SWOT analysis or systems thinking empowers others to analyze their roles and take actions that align with their values. Together, educated and empowered individuals create a ripple effect, bringing awareness and positive influence to the broader system.

- Example: In a school setting, a teacher can introduce students to systems thinking, encouraging them to think critically about their educational environment and explore ways they can contribute to positive changes within the system.

- Action: Host workshops, facilitate discussions, or provide resources on framework thinking and systems analysis. Encouraging dialogue and critical reflection helps build a community of active participants and advocates for positive change.

Conclusion

Every day, we contribute to a vast network of societal systems, often without fully recognizing our roles within them. From the jobs we perform to the purchases we make and even the beliefs we adopt, these systems exert an enormous influence on our lives. But while it’s easy to feel like just another cog in the machine, the reality is that we each have the potential to move beyond passive participation. The key lies in understanding the systems we inhabit, analyzing them critically, and using this awareness to shape a more equitable and fulfilling experience for ourselves and others.

Framework thinking offers practical tools to help us on this journey. By using models like SWOT Analysis and Porter’s Five Forces, we gain insights into our strengths, limitations, and opportunities within systems, as well as the power dynamics at play. This structured approach empowers us to recognize leverage points, identify allies, and take intentional steps toward positive change. With a mindset of continuous improvement, we can implement small, consistent actions that accumulate over time, gradually transforming the systems we interact with.

The question, “Are you someone else’s system input?” challenges us to examine our lives and ask whether we’re shaping the systems around us or simply existing within them. Armed with knowledge, awareness, and critical thinking, we can shift from being passive inputs to active participants — capable of advocating for fairness, transparency, and inclusivity in the structures that shape our world.

Ultimately, the journey toward systemic change starts with each individual. By fostering an understanding of the systems we contribute to and embracing our power to influence them, we can move from being products of these systems to becoming architects of a more equitable future. So, as you navigate the systems around you, consider this: Are you ready to understand, engage with, and ultimately transform the systems you’re a part of?